BY LEN LANGE

It’s too warm for his like in here, the veritable cocoon he’s built from blankets not being his most well thought out plan, what with it being midway through April in New York City. It’s also too quiet. He spends no longer than a moment wrapped uncomfortably in a lack thereof before fumbling for the remote control that should be no further than his nightstand. Thankfully, this assumption is correct.

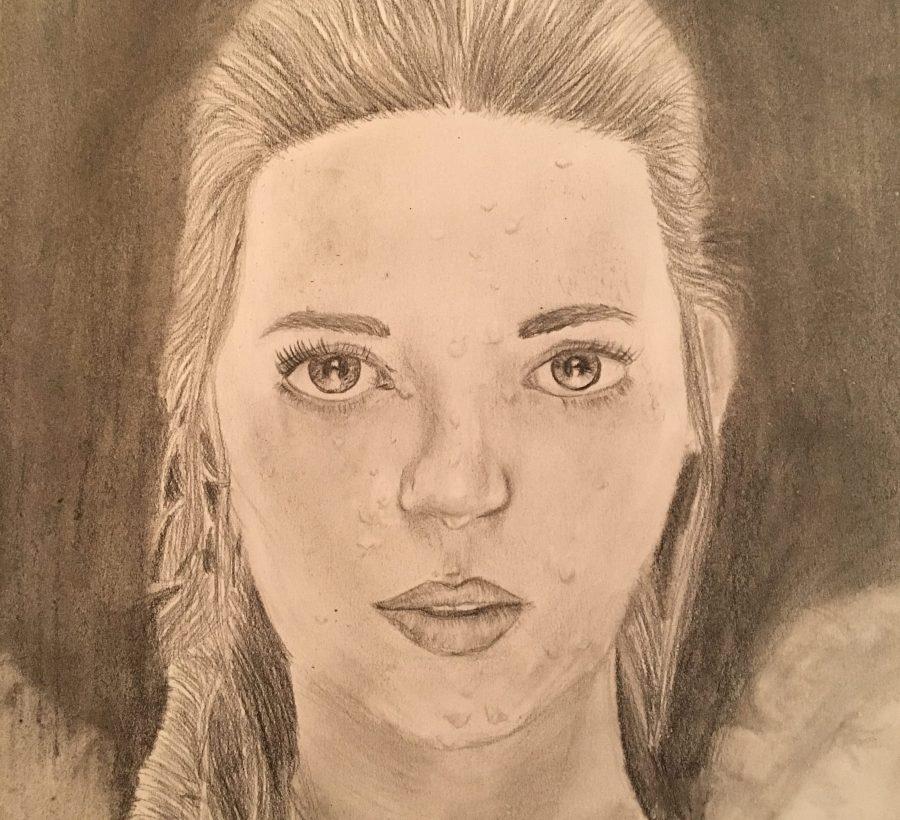

The silence is shattered by white noise, a newscaster that frankly looks half asleep droning on about another arrest, another rebellion, another soon to be execution. Hell, it isn’t even something within his direct vicinity, something in Albany about a girl a few years his senior painting a mural in a train station. He sees it as entirely her own fault, of course, the young woman having quite obviously known the laws and punishments for such crimes. She chose to do something stupid herself, and the rest of the world’s simply going to move on from it. It’s only one more execution, one more failure to abide by basic rules, and one more drop in the ocean. Only a choice few people will be affected by it, so he really sees no reason why such a thing’s worth putting in the news at all. What happened to the girl – Luna LaRue, he reads in the scrolling red bar beneath – is only visual distraction for bored unaffected parties such as himself, and is also likely some spark for some damned fool to do the same thing and receive the same consequence. Unfortunate? Absolutely. His problem? Absolutely not.

He hears a wail from the next room over. He’s only jarred from that questioning sort of reverie by that sound in particular, because there’s only one other person in this apartment. What is his mother crying about? He shakes the blanket pile off of himself, not bothering to turn the television off when he exits the room. His steps are light on wood flooring, pausing tentatively by the entrance to the living room so he can assure he’d heard the sound correctly. He had, and doesn’t understand why. It unnerves him. Another step into the living room reveals the main television, and the exact same channel he’d been watching only moments prior. It couldn’t be that, then. He’d very well know if the LaRue woman was relevant to himself or his mother in the slightest. There’s no harm in asking what it is she was so upset about, so he does precisely that.

“Are you okay?” She jolts visibly, as though she hadn’t expected him to investigate the sound. By any account, she clearly isn’t “okay” in any sense of the word. Perhaps it was a stupid question, then. She turns to face him, looking a veritable disaster for reasons still unbeknownst to him. She sends him a forced, watery sort of smile that only concerns him more.

“Mom.” His tone is something near demanding, though concern is perfectly evident in it. Whatever switched his mother’s tone from the calm collectiveness he’d been met with no more than half an hour ago to this had to have been a phone call from the police station, or something equally hopeless. He can feel his chest tighten slightly. It takes her a moment to reply, but it frankly helps no part in his bewilderment.

“Have you been watching the news, Will?” He nods. Is this about the girl from Albany?

“So you saw the girl who-” She can’t finish the sentence without choking up. This doesn’t make any sense, not in the slightest. He doesn’t know that girl.

“I did.” He’s on edge right now, he can feel it. The girl who’d just been on the news, the one who’d passed away, knew his mother somehow?

She pulls in a deep, rattling breath before speaking more. “Alright, well, that girl was someone I know well. You should’ve known her, too.”

Why? This time she doesn’t simply choke up. Another sob is pulled from her, as loud as the first. He doesn’t understand. Unsure as to what he should be doing in this sort of utterly befuddling situation, he doesn’t move from wall he’s been standing against. He’s wordless to this, and the next words are hers. They’re sniffly and raw, but it’s her that speaks first.

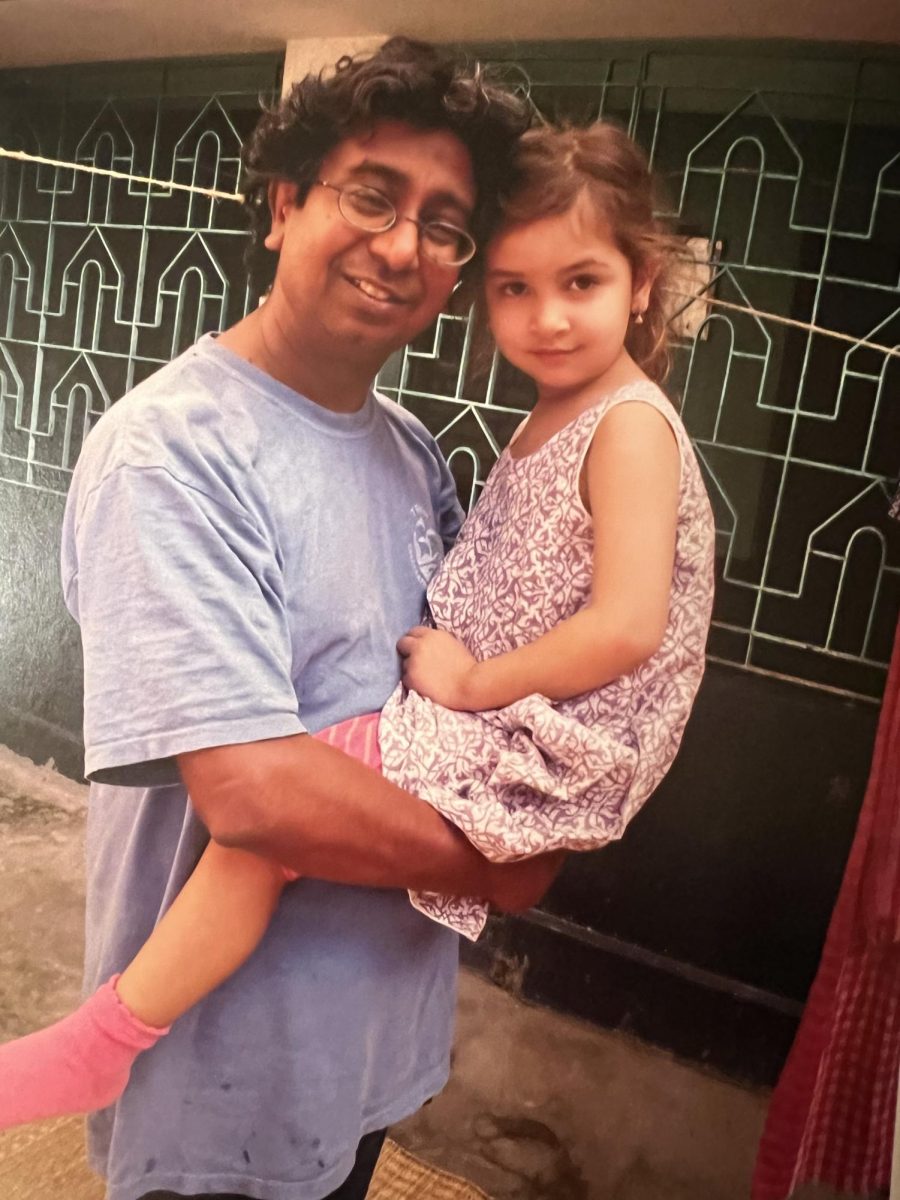

“That girl is my daughter with your dad. She’s- She was your sister. You- You only saw her when you were a tiny baby, huh? Really little.”

What? What sort of person fails to mention this? He doesn’t know how to react to any of this. He has a sister and he’s met her. Except he doesn’t have a sister, does he? Not anymore. The girl on the television, who’s story’s even blipped off now, as a cursory glance toward what’s now a weather forecast makes evident; that girl was his sister in life and death. That girl he’d mentally chided hardly fifteen minutes ago for foolish rebellion is… his sister. He has a sister. He had a sister. LaRue. Something LaRue. That girl was his sister. He was related flesh and blood to that girl. That dead girl who painted a mural in a train station in Albany was his mother’s other child. That girl was his father’s child. His sister he doesn’t know. His father he doesn’t know. His family in Albany, New York. The dad who doesn’t want to see him. The sister he won’t get to see. In Albany. On the news. Out of his life. In the public eye for only a moment.

“I should’ve told you before, sweetie. This is on me.” He remains stunned into silence. She doesn’t say anything after that, instead gesturing vaguely for him to sit beside her on the sofa. It takes him another moment leaning on the wall to properly do anything at all, and his steps on the carpet are the only muffled sounds he registers as he crosses the room. He’s still mulling over the newfound mess in his head, so no words leave him as he sits down. Later, he’d come to realize he isn’t exactly sure how long they’d sat there in abnormally comfortable silence.

***

He’s still entirely uncomfortable with the idea as a whole for a time after, through that week and the announcement of a funeral they’d head north a few hours to get to. May 9th was the scheduled date. Two weeks doesn’t seem to take long to come to pass when one’s dealing with the sort of revelations he’s been confronted with lately, and the time between when he’d seen the name on TV – Luna LaRue; they’d shared a surname until he was five. Will LaRue sounds foreign and uncomfortable on his tongue – and sitting in the passenger’s seat for what had to be about three hours.

His eyes have been flitting between anything and everything in and outside the car. It’s a stupid habit, as though some sort of visual avoidance can deny the fact that he frankly doesn’t know how he should react to this sort of confrontation. He’s been to a funeral, of course, but he’d known the person, at minimum. He was within his rights to be upset. Now he’s frankly confused, more than anything else. Confused feels unnatural, but too natural at once. He shouldn’t go to this. He’s going to be surrounded by people in mourning over a lost daughter, lost cousin, lost friend, lost past schoolmate, even. He can’t say he lost a sister, he never knew he had one!

His thoughts are loud and pounding against his skull like a migraine, though his expression remains serene. His eyes haven’t focused on anything, staring blankly out the window without a trace of the turmoil that’s coming to a frustrated boil somewhere just under his skin. His eyes flit briefly to his mother, her knuckles white on the steering wheel, eyes frozen on the freeway. He sees no reason to speak. He has no reason to speak. He doesn’t speak. He’s far more fascinated with the uniform green of almost summer trees on the roadside than broaching the subject. He’s already debated talking about something else entirely, but a sinking, falling, drowning, feeling in the pit of him disallows that option entirely. It’d be wrong.

The only sound in the vehicle is the light, typically unnoticed whirring of the air conditioner that drones tirelessly. He can’t not notice it in this particular instance. Any sort of silence has all but deafened him since childhood, and unable to stand it he whined and babbled to fill it. That at least, is what his mother told him when he was ten and needed to know what little Will LaRue Moreau was like for a school project. He doesn’t care to remember the details. That project couldn’t have been all that accurate in retrospect, what with the missing information he’d only so recently begun recovering parts of. It’s an awful feeling, not knowing something. That could also be hindsight speaking just as easily so, if not even more likely the case.

The inner workings of his psyche are far louder than any sound in the vehicle, and one thought is blurring into the next faster than the green mass whipping past on the side of the freeway. He loses track of their location for at least the final hour before the car pulls into some Courtyard Marriot, and he sees no reason to acknowledge the odd feeling in his legs when he finally does stand up.

***

(To be continued)